First things first – before we start discussing different strategies in remedial teaching, in my opinion, it would be a great idea to walk through some common mistakes and misconceptions related to mathematics. As we agreed in our previous post, that every child has its own way of learning; in this post, we shall see how each child makes mistakes differently. 🙂 And yes, mistakes are different from misconceptions. This is where a teacher needs to be sensitive and sharp enough to differentiate between the two. Let us begin the diagnosis!

The Difference Between a Mistake and Misconception:

Here is a Grade 2 student’s response to a given set of questions: try to identify the misconception in the following two problems.

a. Use < as 'is less than' and > as ‘is greater than’ signs to compare and order numbers:

- 73 < 79

- 25 = 25

- 45 < 56

- 51 < 49

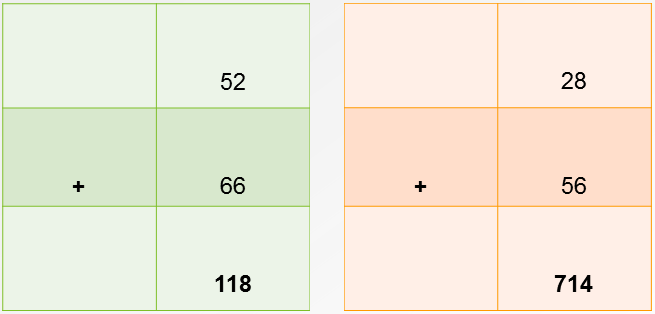

b. Add two digit numbers:

By now you would have understood the learner’s misconception; somewhere s/he is struggling with the basic concept of place value, isn’t it?

Just look at the a.4. (51 < 49), the learner seems to have compared the one's place values; 1 in 51 with the 9 in 49 and thus, we see the alligator's mouth open towards 49 instead of 51. A similar mistake due to misconception can be seen in b.2. (28 + 56 = 714), wherein the one's place has been added to get 14 and the ten's place adds up to 7 - instead of carrying 1 for addition in the ten's place, it remains below, and hence, getting a result of 714 instead of 84. If you have observed something else too, please do mention in the comment below. As a teacher correcting tons of pages daily and beginning to get insensitive over a period of time, the teacher would not mind putting a big cross to the above answers. With good intent, s/he would also give additional worksheets to solve (most of the time downloaded from the internet). Here is another thing about ready made stuff: the beautifully designed mark sheet or score card may even say that the learner's understanding in ‘comparing and ordering numbers’ is 75% and is likely to be promoted to next level. Now as s/he progresses to the next grade, the learner has to deal with 3 to 4 digit numbers. And the new errors would look like this ‘1105 < 999'. In this case, the ready made stuff didn't help in learning but surely in the promotion (of error). The learner is likely to continue to get such answers unless someone takes a little moment to reflect as to how is s/he arriving at the incorrect answer consistently. Which according to the learner is the correct answer but there is no iota of doubt in the learner's mind! Here is the fine line between the two... Remember mistakes are usually one-off. If the problem is shown again to the learner, s/he may figure out the mistake because mistakes are usually done due to carelessness. But if the learner continues to make similar error confidently then it has to do with misconception. I love understanding things this way - ‘All misconceptions lead to mistakes but all mistakes are not misconceptions’.

Check out some interesting examples on misconception from math4teaching.com by author Erlina. Couple of them given below:

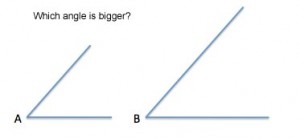

Did we not learn that the greater the opening of an angle, the bigger it is? So, angle A is less than angle B in the figure below.

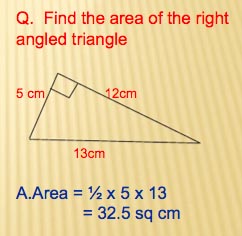

Isn’t it that the base is the one lying on the ground?

Whether you are a maths teacher or not, in life we all make mistakes. So if we keep making mistakes, we keep learning from them. But remember, they get serious if hidden or done consistently and consciously.

Here is an interesting idea about multiplication – ‘If we multiply two numbers, we get a bigger number’. Tell us if this is a true fact or a misconception and do justify your answer in the comment section below.

I am eagerly waiting to discuss ‘Remedial Teaching Strategies’ in our next post.

September 21, 2017 at 9:42 am

Wonderful diagnosis of the entangled ideas of mistake and misconception. I’m eager to read the next topic as well!